Danny Jones was a professional rugby player. One day in the middle of a game, he died from sudden cardiac arrest, at the age of 29. Layton Cooper was a businessman. He wasn’t overweight, didn’t smoke, rarely drank and kept fit by walking his dog. One day he collapsed in the office and never recovered, at the age of 35. Tests revealed he had ischemic heart disease, a condition where not enough blood is supplied to the heart. Both cases were unusual, because heart disease typically doesn’t strike people so young, unless it’s associated with less than optimal lifestyle choices like an unhealthy diet, lack of exercise or smoking. Unknown to both of them, these two men had one thing in common, a genetic condition that increased their risk of heart attacks. Familial hypercholesterolemia is an inherited condition where people develop high cholesterol levels in the blood and it dramatically increases the risk of having a heart attack at an early age. An estimated 1.3 million people in the US have familial hypercholesterolemia, but 90% of these cases are either undiagnosed or misdiagnosed until they have a heart attack, in which case the diagnosis came too late.

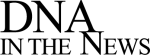

While the heart attacks are ultimately caused by cholesterol build-up in the blood vessels, familial hypercholesterolemia is actually an inherited genetic disease. We all consume cholesterol, a fat-like substance found in large amounts in eggs, poultry, meat or fish and in smaller amounts in other foods. Once in the bloodstream, cholesterol is transported mainly by proteins called low-density lipoproteins (LDLs). LDL-cholesterol has been dubbed “bad” cholesterol, because they can build up in the walls of blood vessels, particularly the ones that provide blood to the heart and cause heart disease. People with familial hypercholesterolemia have genetic changes that elevate LDL-cholesterol levels in the bloodstream. This is what increases their risk of heart problems by 20-fold, because the more LDL-cholesterol there is in the blood, the more likely they will clog blood vessels.

Three genes, LDLR, PCSK9 and APOB, are linked to familial hypercholesterolemia and they all affect the movement of cholesterol from the bloodstream into the body’s tissues. Genetic changes found in LDLR and PCSK9 decrease the removal of LDL-cholesterol from the bloodstream. The third gene, APOB, gives instructions to make a protein known as ApoB-100, a building block of LDLs. Changes in the ApoB-100 protein prevents LDL-cholesterol from being removed from the bloodstream properly. The ultimate result in all cases is higher levels of LDL-cholesterol levels in the bloodstream. However, in contrast to the 34 million people in the US with elevated cholesterol levels caused by poor diet, lack of exercise, obesity or smoking, people with hypercholesterolemia suffer from high cholesterol levels because they have inherited certain genetic defects.

About 1 in 200 to 1 in 500 people around the world are affected by familial hypercholesterolemia, and when left untreated, it can be life threatening. However, of the 1.3 million cases in the US, only about 10% are diagnosed. That’s over a million young, fit, non-smoking Americans living with this condition, unaware of their risk of heart attacks. A person who inherits two defective copies of these genes is at very high risk of experiencing a severe cardiac event as early as in their 20’s. For this reason, familial hypercholesterolemia has been called the silent killer. Even though it is a symptom-less disease, familial hypercholesterolemia can be easily diagnosed with just a simple DNA test. Early detection and diagnosis offers the best possible outcome to people with this disease, because changes in lifestyle choices and medications that lower LDL-cholesterol levels can have a profound impact on a person’s risk of heart disease. You may have no control over the genes you inherit, but it is up to you to decide how much you will let them control your life.