Researchers use a new method to extract DNA from preserved samples, opening the door to exploring the DNA of millions of preserved specimens housed at museums.

A slice of history

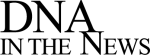

Washington, London, Chicago, Vienna, and Beijing are just some of the cities that are home to natural history museums with perfectly preserved biological specimens. In some cases, these samples represent the last remnants of long extinct species.

This is why the ability to access the DNA of these preserved organisms is of such importance. Their DNA stories can give us insight into the environments, diets, and even the microbiomes from the exact moments when these samples were preserved.

The problem with preserved DNA

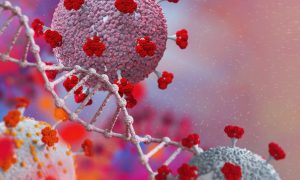

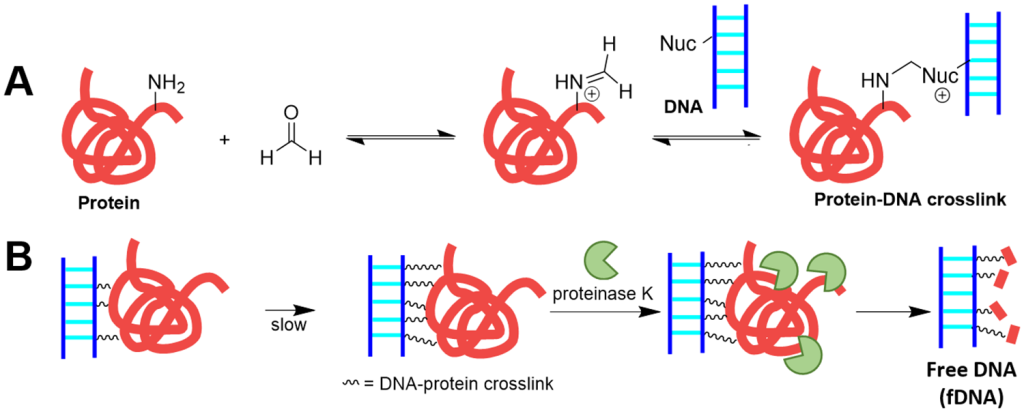

Formalin has been the preservative of choice for more than 150 years for fixing biological samples. A disinfectant and an antiseptic, formalin stops parasites from growing on tissue samples, keeping them in ‘perfect’ condition.

The problem with formalin is that formalin fixation (preservation) can damage DNA by breaking the DNA sequences into fragments. Not only that, formalin can interfere with the processes used to recover and analyze DNA, making it very difficult to access the valuable genetic information trapped inside these preserved museum samples.

These issues are further compounded by the fact that most of the current methods for recovering DNA from preserved samples have to be performed at high temperatures (49°C or 120°F) and take a long time (>17 hours), which increases the likelihood of further damage to the DNA samples.

The vortex fluidic device

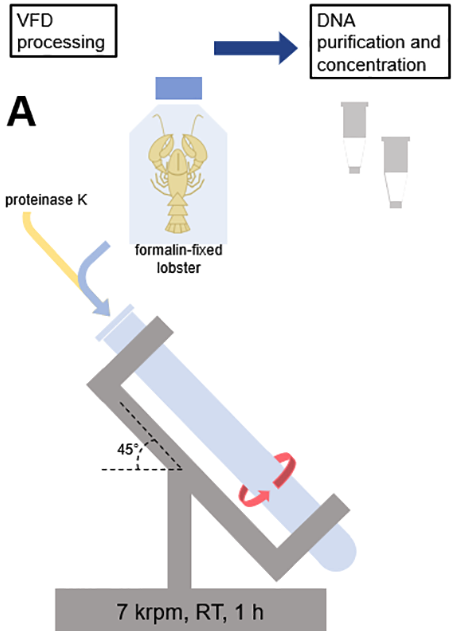

The above problems are only some of the reasons behind why researchers in this study looked into a recently patented technology called the vortex fluidic device (VFD) to tackle the problem of fragile samples.

This technique’s first claim to fame was in 2015 with the “unboiling a boiled egg” experiment, which introduced the idea that mechanical forces in a thin microfluidic device can reshape proteins to gain back their original structure.

In this case, researchers predicted that the power of VFD can be used to accelerate the activity of the enzyme used during DNA extractions, reducing the required time to recover DNA, and thereby increasing the yield.

Enter the lobster

The researchers began by preserving an adult male lobster purchased from a fishery in Boston using standard practices. This sample was stored at room temperature for one month before shipping it to the study location at the University of California, Irvine. All subsequent experiments were performed using this sample, which was in preservative for two years.

Researchers found that compared to conventional methods, VFD reduced the DNA extraction time from more than 17 hours to less than two hours, which would decrease the amount of damage to the DNA. Perhaps more importantly, they showed that DNA collected using this new, faster method was amenable to standard DNA sequencing protocols as well as DNA quantifying protocols, opening a whole new world of possibilities for obtaining DNA samples from millions of fixed samples housed in natural history museums around the world.

DNA secrets revealed

Since its invention, the VFD has made an incredible impact on several different biomedical fields. The ability to unravel the genetic stories hidden in samples dated more than 150 years can now be added to its list of accomplishments.

Scientists postulate that more than 400 million formalin-fixed samples are available at natural history museums from around the world. Having the ability to unravel the DNA stories hidden within these samples will give scientists with an invaluable source of information to improve our understanding of the world around us.

Reference

Vortex fluidics-mediated DNA rescue from formalin-fixed museum specimens